Association between dementia diagnosis at dialysis initiation and mortality in older patients with end-stage kidney disease in South Korea

Article information

Abstract

Background

The prevalence of dementia is 2- to 7-fold higher among patients with end-stage kidney disease (ESKD) than among the general population; however, its clinical implications in this population remain unclear. Therefore, this study aimed to determine whether comorbid dementia increases mortality among older patients with ESKD undergoing newly initiated hemodialysis.

Methods

We analyzed data from the Korean Society of Geriatric Nephrology retrospective cohort, which included 2,736 older ESKD patients (≥70 years old) who started hemodialysis between 2010 and 2017. Kaplan-Meier survival and Cox regression analyses were used to examine all-cause mortality between the patients with and without dementia in this cohort.

Results

Of the 2,406 included patients, 8.3% had dementia at the initiation of dialysis; these patients were older (79.6 ± 6.0 years) than patients without dementia (77.7 ± 5.5 years) and included more women (male:female, 89:111). Pre-ESKD diagnosis of dementia was associated with an increased risk of overall mortality (hazard ratio, 1.503; p < 0.001), and this association remained consistent after multivariate adjustment (hazard ratio, 1.268; p = 0.009). In subgroup analysis, prevalent dementia was associated with mortality following dialysis initiation in female patients, those aged <85 years, those with no history of cerebrovascular accidents or severe behavioral disorders, those not residing in nursing facilities, and those with no or short-term hospitalization.

Conclusion

A pre-ESKD diagnosis of dementia is associated with mortality following dialysis initiation in older Korean population. In older patients with ESKD, cognitive assessment at dialysis initiation is necessary.

Introduction

Cognitive dysfunction, associated with dementia and Alzheimer disease (AD), is a major health problem among older adults worldwide. The prevalence of cognitive dysfunction increases with age and is known to double every 20 years after 65 years of age [1]. Global population aging is expected to lead to an increase in the number of people with dementia to approximately 100 million by 2050 [2]. However, currently, there are no definitive therapeutic options for AD [3]. Identifying factors that increase the risk of dementia and focusing on ameliorating these risk factors are important.

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is a medical condition in which kidney damage occurs or kidney function gradually worsens, and is usually apparent as one ages [4]. Increasing age is associated with an increased risk of CKD as well as that of cerebrovascular disease [5]. Various studies have suggested that CKD and cognitive impairment are mutually associated [6,7]. Existing studies have shown an association between dementia and CKD in patients with end-stage kidney disease (ESKD) undergoing dialysis [8], and even in those with mild-to-moderate CKD [9–11]. The Cardiovascular Health Cognition Study [9] revealed that moderately decreased renal function was associated with vascular-type dementia but not with AD, even in individuals with preserved kidney performance. Patients with ESKD and cognitive dysfunction are more susceptible to early mortality and dialysis withdrawal, making decisions regarding dialysis treatment particularly challenging. A more patient-centered approach has recently been proposed, emphasizing palliative care during dialysis for patients with limited life expectancy in the hope of reducing their suffering [12]. Consequently, the Renal Physician Association guidelines recommend considering discontinuation of dialysis for dementia patients who have lost awareness of themselves and the environment [13].

Dementia, a significant cause of death and disability among older adults, has a 2- to 7-fold higher prevalence among patients with ESKD than among the general population [14–17]. Although existing research on outcomes in dialysis patients with dementia primarily focuses on prevalent ESKD, there is a dearth of data on the outcomes of patients diagnosed with dementia prior to the development of ESKD (among those starting dialysis). Previous studies examining the clinical implications of dementia in the CKD population have included a few participants or defined dementia based on clinical diagnosis [8–11]. Therefore, this study aimed to determine whether comorbid dementia increases mortality among older ESKD patients newly started on hemodialysis using nationwide cohort data.

Methods

Study population

The dataset utilized in this study was sourced from the Korean Society of Geriatric Nephrology (KSGN), encompassing a cohort of 2,736 older patients with ESKD (≥70 years) for whom hemodialysis had been initiated. Patients were registered at 17 university hospitals in Republic of Korea between 2010 and 2017. Individuals who initiated emergency hemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis and those lacking documented death information were excluded from the dataset. The factors considered in this study included the patient’s age, sex, any existing comorbidities such as diabetes mellitus (DM), cardiovascular disease, cerebrovascular accidents (CVA), hypertension (HTN), dementia, severe behavioral disorders other than dementia, liver cirrhosis, and cancer, along with medication history and history of hospitalization, the cause of ESKD, and the type of vascular access at dialysis initiation. Additionally, serum albumin levels, white blood cell count, hemoglobin, glucose, blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, total bilirubin, and total cholesterol levels were measured at dialysis initiation. In this study, dementia was defined as the use of dementia medications under the Korean government’s health insurance service policy.

Outcome measurement

The main objective of this study was to compare the mortality risk associated with the dementia and non-dementia groups. Mortality data were obtained from the Statistics Korea (MicroData Integrated Service, On-demand, 20,180,619; https://mdis.kostat.go.kr).

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Patient clinical data were collected after receiving approval from the Institutional Review Board (IRB) for each study period (Supplementary Table 1, available online). The need for obtaining patient informed consent was waived by the relevant IRBs. This study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. All personal identifiable information is adequately protected.

Statistical analyses

Continuous and nominal variables are expressed as means with standard deviations. Variables with normal distribution were analyzed using the Student t test, independent two-sample t test, and analysis of variance. Data with an abnormal distribution were analyzed using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test. Categorical variables were expressed as frequencies and percentages and analyzed using the chi-square or Fisher exact test. Differences in survival rates between groups were compared using Kaplan-Meier survival curves and the log-rank test. Cox proportional hazard models were used to examine mortality based on the risk factors. Furthermore, the variance influence factor was used to confirm multicollinearity.

For sensitivity analysis, propensity score matching (PSM) and standardized differences were employed to juxtapose the baseline traits of the two study groups. Certain variations in the initial characteristics were observed between the groups, which could potentially skew the estimation of the impact of dementia on mortality. Characteristics exhibiting these variations included sex, age at initiation, DM, HTN, CVA, and severe behavioral disorders. To mitigate this bias, often observed in observational studies, covariates were balanced across both groups using propensity scores. The nearest-neighbor matching approach in conjunction with a 1:1 matching algorithm without replacement was implemented to identify matches for each individual in the dementia group. PSM was performed using the PSM Match It application, an open-source package in R (version 4.2.2; R Foundation for Statistical Computing, http://www.r-project.org). Kaplan-Meier survival curves and life tables were generated for both the dementia and non-dementia groups.

Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS version 26 (IBM Corp.) and R programming language version 4.2.2.

Results

Baseline characteristics

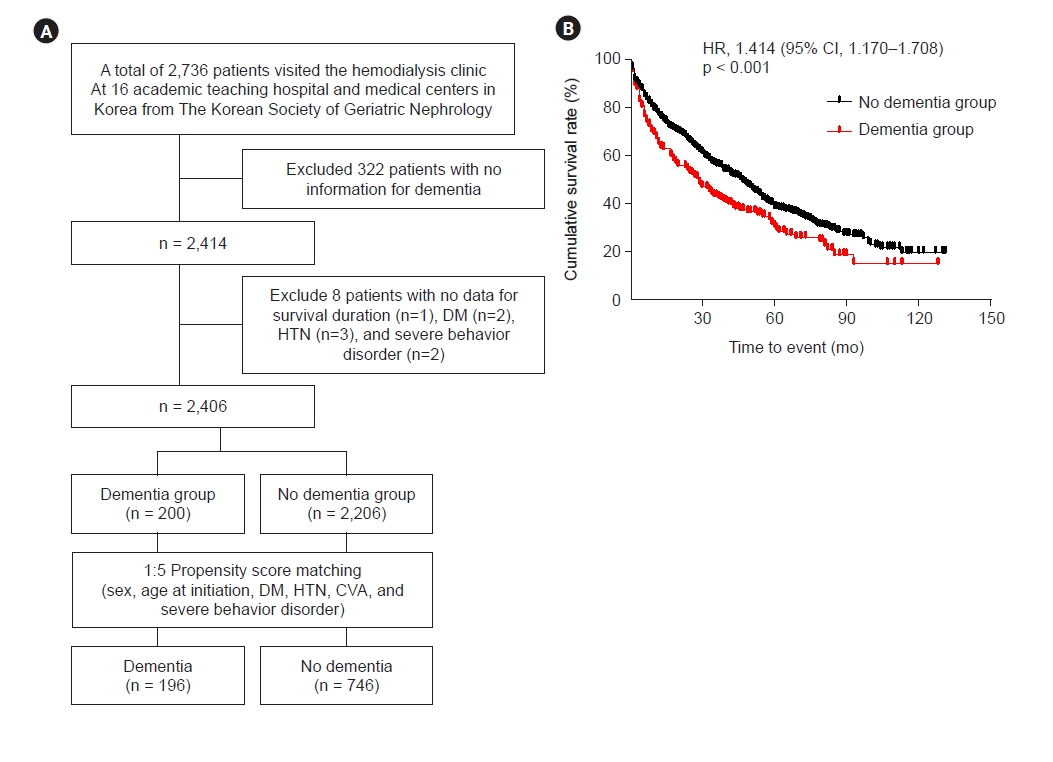

Fig. 1 shows the patient flowchart for all study groups. A total of 2,736 patients were recruited from 17 medical centers; after excluding patients with missing data, 2,406 patients were finally enrolled. In total, 200 patients (8.3%) were diagnosed with dementia at the time of dialysis. During our study, we observed 1,472 deaths, with a median follow-up duration of 3.1 years. Table 1 shows the basic characteristics of the cohort, according to the presence or absence of dementia. At the time of initiation of dialysis, the average age (dementia group, 79.6 ± 6.0 years; non-dementia group, 77.7 ± 5.5 years) and the proportion of female patients in the dementia group were higher (dementia group, 55.5%; non-dementia group, 43.9%) than those in the non-dementia group. DM was the most common cause of ESKD in both groups. The dementia group differed significantly from the non-dementia group in terms of vascular access, comorbidities with CVA, severe behavioral disorders, serum albumin levels, and serum creatinine levels. Hospitalization within 6 months before dialysis or 6 months to 1 year before dialysis and living in a nursing facility at the time of dialysis were more common in the dementia group.

Study flow chart.

Missing data for variables pertaining to dementia (n = 322), survival duration (n = 1), diabetes mellitus (DM; n = 2), hypertension (HTN; n = 3), and severe behavioral disorders (n = 2).

Survival analysis and risk factor analyses for mortality using Cox regression

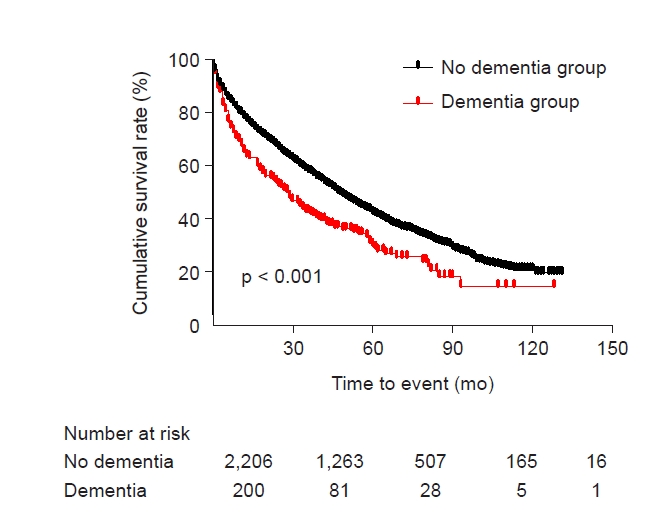

Kaplan-Meier survival curve analysis showed that the survival rate was lower in patients with a pre-ESKD diagnosis of dementia at the initiation of dialysis than in those without dementia (Fig. 2). In Cox regression analysis, the unadjusted hazard ratio (HR) of the presence of dementia for all-cause mortality was 1.503 (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.263–1.788; p < 0.001), and this association remained consistent after multivariate adjustment (HR, 1.268; 95% CI, 1.060–1.516; p = 0.009) (Table 2).

Kaplan-Meier survival curve.

Survival rates of patients with dementia (dementia group) and patients without dementia (non-dementia group) are presented using Kaplan-Meier survival curves, and the difference in survival rate between groups was compared using the log-rank test (Mantel-Cox). p < 0.001.

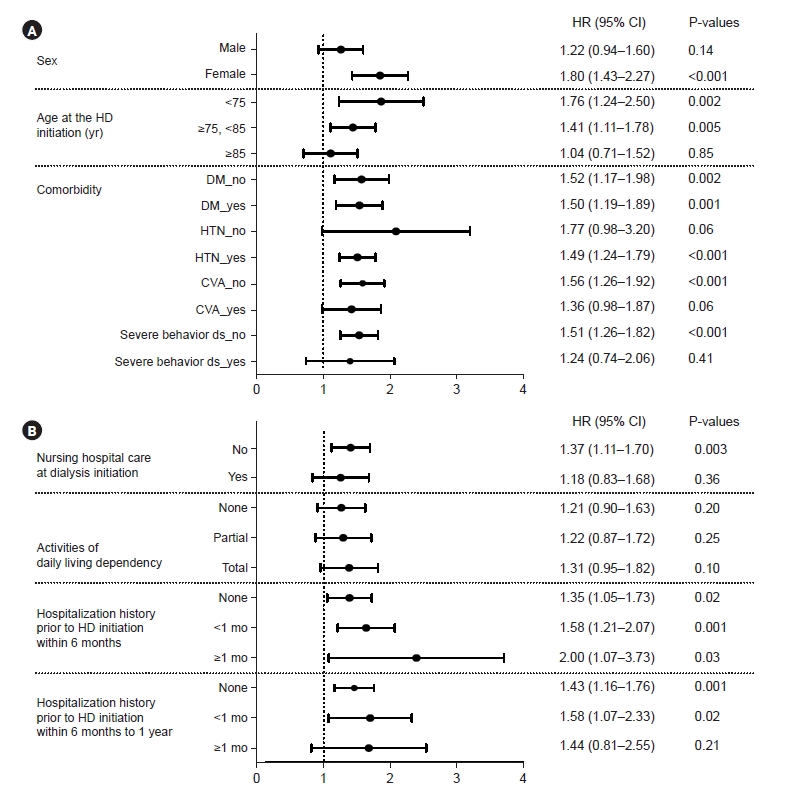

Subgroup analysis

The adjusted HRs (95% CIs) for the presence of dementia for all-cause mortality in the selected subgroups are shown in Fig. 3. Dementia was significantly associated with all-cause mortality in the following subgroups: female patients, patients younger than 85 years of age, patients with HTN, and those without CVA or severe behavioral disorders. Prevalent dementia in patients who did not reside in a nursing facility at the start of dialysis and had a history of no hospitalization or short-term hospitalization before dialysis was more closely associated with mortality following dialysis initiation, whereas there was no relationship between dementia and mortality according to differences in dependency on activities of daily living (ADL).

Sensitivity analysis using propensity score matching

Fig. 4 shows Kaplan-Meier survival curve obtained after 1:5 PSM using variables including sex, age at dialysis initiation, DM, HTN, CVA, and severe behavioral disorder. Dementia was a significant predictor of all-cause mortality (HR, 1.414; 95% CI, 1.170–1.708; p < 0.001) in the propensity-matched cohort.

Survival analysis in the propensity-matched cohort.

(A) Study flowchart, including 1:5 propensity score matching. (B) Kaplan-Meier survival curve and HRs (95% CIs) of the presence of dementia for all-cause mortality in the propensity-matched cohort.

CI, confidence interval; CVA, cerebrovascular accidents; DM, diabetes mellitus; HTN, hypertension; HR, hazard ratio.

Discussion

In this study, we found that in Korea, the prevalence of dementia among older patients with ESKD who started hemodialysis was 8.3%. A pre-ESKD diagnosis of dementia was associated with a 50% increase in the risk of post-ESKD mortality, and this association remained consistent after multivariate adjustment and PSM. In the subgroup analysis, prevalent dementia was more closely related to mortality following dialysis initiation in female patients, patients younger than 85 years, patients with no history of CVA or severe behavioral disorders, those not residing in nursing facilities, and those with no hospitalization or short-term hospitalization.

These findings are consistent with those of recent studies, which reported that the presence of dementia before dialysis increased the risk of postdialysis mortality by 19% to 30% [18,19]. Multiple factors, such as increased cardiac and cerebrovascular risks [19], frailty [14,20], impeding treatment adherence [21], and comorbidities [22], may contribute to post-ESKD mortality in dementia. Interestingly, dementia in the subgroup with comorbid CVA or severe behavioral disorders was not significantly associated with mortality in this study. In addition, ADL level, a frailty indicator, was not significantly related to mortality in incident hemodialysis patients with prevalent dementia. A recent prospective study demonstrated a significant interaction between cognition and frailty in association with hospitalization and death in prevalent hemodialysis recipients [14]; however, in our study, ADL did not appear to be important for dementia-related mortality in incident hemodialysis patients. This study showed that increased mortality following hemodialysis in patients with prevalent dementia may be more attributable to dementia itself or other factors than to increased cerebrovascular risk, frailty, or comorbidities.

In the subgroup analysis, the relationship between a pre-ESKD diagnosis of dementia and mortality following dialysis initiation was more noticeable among female patients than male, and in the younger subgroup (<85 years old) than in the older subgroup. Regarding differences in mortality by sex, previous studies have demonstrated inconsistent sex effects according to various dementia diagnoses [22]. In our study, among patients older than 85 years, the group with dementia had no cases of metastatic or ongoing malignancies, whereas the group without dementia included cases of comorbid malignancies, which may have influenced the correlation between dementia and mortality. If patients are hospitalized in a nursing facility at the start of dialysis, their prognosis is poor with or without dementia. However, mortality increases in patients with dementia if they are not hospitalized in a nursing facility at the time of dialysis initiation. In the group with a history of long-term hospitalization, particularly within 6 to 12 months prior to starting dialysis, mortality was not associated with dementia, suggesting that long-term hospitalization per se increases the risk of death regardless of dementia. A correlation was observed between dementia and mortality in the groups with or without short-term hospitalization. Consequently, an increase in mortality risk after dialysis due to dementia should be considered, even in patients who do not reside in nursing facilities or those who do not have a history of long-term hospitalization.

Various factors can exacerbate the progression and prognosis of dementia in patients undergoing hemodialysis. A recent cohort study of older hemodialysis patients revealed that increased dialysis clearance is associated with a lower risk of developing dementia [23]. Subclinical cerebral hypoperfusion and edema can accelerate cognitive decline and contribute to dementia via recurrent events of rapid hemodynamic and metabolic alterations that occur during hemodialysis sessions [24]. Vascular factors, including arteriosclerosis, may contribute to the increased risk of AD [25] and vascular dementia [17] in older patients undergoing hemodialysis. Further prospective studies are needed to identify modifiable factors associated with reduced mortality and cognitive decline in patients with dementia undergoing hemodialysis.

Although the severity of dementia was not investigated in this study, it is surprising that more than 8% of patients with ESKD exhibit dementia at the time of hemodialysis initiation in South Korea. A previous study based on the Korean Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service database between 2005 and 2008 showed that 3.0% of patients aged >65 years had dementia at the time of hemodialysis initiation [19]. The lower prevalence of dementia compared to that in our study is possibly due to underdiagnosis during the coding procedure in the previous study. In addition, the Korean population has been rapidly growing older, and the age-standardized annual prevalence rate of AD in Korea has increased from 3.17 in 2006 to 15.75 in 2015 (events per 1,000 persons) [26]. A cohort study of veterans in the United States conducted between 2007 and 2011 revealed that 3.0% of incident dialysis patients had dementia, highlighting that nearly 50% of patients with dementia died within a year of dialysis initiation [18]. Given the increased prevalence and aggravated mortality risk associated with dementia in patients with ESKD, cognitive assessment of patients with ESKD before dialysis initiation may be instructive. The presence of dementia before starting dialysis is a decisive factor in the choice between dialysis and conservative management. Nevertheless, conservative kidney management (CKM) in Korea remains challenging owing to insufficient reimbursement policies, distorted public awareness, and limited access to a multidisciplinary team. CKM should be considered as an alternative to dialysis, especially in patients with severe dementia and a relatively high risk of death.

Variables specific to the older cohort, such as ADL, nursing facility residence at the start of dialysis, history of hospitalization within a year prior to dialysis, and their relationship with dementia, were explored in this study. Our study provides novel insights that have not been previously described. In addition, this study examined the characteristics of older Korean patients beginning dialysis and revealed an increased risk of death following dialysis among those with dementia. These findings may guide future treatment options for Korean ESKD patients. However, this study was limited by its retrospective and observational nature, although it was conducted as a large-scale multicenter nationwide study in Korea. To address this, the KSGN has been recruiting and conducting an ongoing trial in older predialysis patients with CKD since 2019, and the results of this prospective study will be published in the near future. Another limitation of this study is that more than 5% of the data on ADL and hospitalization history were missing. Finally, our definition of a person with dementia was based on people taking dementia medications and having a dementia diagnosis code. A limitation of this study is that it did not investigate specific drugs. It is worth noting that dementia medication prescriptions typically require a Mini-Mental State Examination test for insurance coverage. Therefore, in our study, the presence of a medication prescription was used as a diagnostic definition. Therefore, the possibility of misclassification and uninsured prescriptions of these drugs cannot be ruled out. Furthermore, data on dementia subtypes were not included in the analysis.

In conclusion, a pre-ESKD diagnosis of dementia is associated with mortality following dialysis initiation among older patients in Korea. This relationship was more prominent in female patients (than in male patients) and in the subgroup aged <85 years (than in the subgroup aged >85 years). Therefore, cognitive assessment prior to dialysis initiation is required for older patients with ESKD, and careful monitoring and management are required to reduce mortality risk in patients with dementia. Further studies are required to compare the prognoses of different treatment options for ESKD in older patients with dementia.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary data are available at Kidney Research and Clinical Practice online (https://doi.org/10.23876/j.krcp.23.151).

Notes

Conflicts of interest

All authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding

This work was supported in part by a Cooperative Research Grant 2019 from the Korean Society of Nephrology and the Ulsan University Hospital Research Grant (UUH-2020-08). This research was also supported by a grant from the Patient-Centered Clinical Research Coordinating Center (PACEN) funded by the Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (grant number: HC21C0059).

Data sharing statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.

Authors’ contributions

Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision: SRK, KDY

Data curation: BMY, SK, SRK, KDY

Formal analysis: BMY, SRK

Funding acquisition: YAH, KDY, SHK

Investigation, Resources: WYP, JHC, BCY, MH, SHS, GJK, JWY, SC, YAH, YYH, EB, IOS, HK, WMH, SJS, SHK

Writing–original draft: BMY, SK, SRK, KDY

Writing–review & editing: All the authors

All the authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgements

Korean Society of Geriatric Nephrology (KSGN) list of consortium members and their affiliations as follows: Soon Hyo Kwon, Soonchunhyang University Seoul Hospital, Seoul, Korea (President); Sungjin Chung, Yeouido St. Mary’s Hospital, College of Medicine, The Catholic University of Korea, Seoul, Korea (Vice-president); Byung Chul Yu, Soonchunhyang University Bucheon Hospital, Bucheon, Korea (Secretary General); Woo Yeong Park, Jang-Hee Cho, Miyeun Han, Sang Heon Song, Gang-Jee Ko, Jae Won Yang, Yu Ah Hong, Young Youl Hyun, Eunjin Bae, In O Sun, Hyunsuk Kim, Won Min Hwang, Sung Joon Shin, and Kyung Don Yoo (available at http://gsn.or.kr/common_files/about_03.asp 9 May 2022, This is the current list of executive committees from the KSGN official homepage).