Introduction

With the global population aging, the number of patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) is increasing [

1]. Between 2005 and 2015, the number and prevalence of CKD in the adult Japanese population increased from 13.3 million to 14.8 million and from 12.9% to 14.6%, respectively [

2]. Diabetes, hypertension, old age, dyslipidemia, obesity, smoking, and lifestyle-related diseases are well known to increase the risk of CKD, which is not only the primary risk factor for end-stage kidney disease but also one of the most significant risk factors for cardiovascular disease (CVD) [

3–

5]. Delaying disease progression, reducing complications, and improving quality of life are the main objectives of CKD therapy. Therefore, multifactorial intervention, including blood pressure control and glycemic control, in combination with lifestyle modification and dietary advice, with multidisciplinary team-based integrated care, has been highlighted as an important therapeutic strategy to reach this objective [

6].

The comprehensive treatment model is an interdisciplinary medical care system that integrates a variety of professions with different but complementary abilities, knowledge, and experience to improve healthcare and produce the best results to suit patients’ needs both physically and psychologically [

7,

8]. In Japan, the Certified Kidney Disease Educator (CKDE) system was established by the Japan Kidney Association (JKA) in 2017 to prevent disease progression and improve and maintain the quality of life for patients with CKD [

9]. Nurses, registered dietitians, and pharmacists who were trained and meet certain requirements are eligible for qualification as a CKDE [

9]. However, even if multidisciplinary interventions are provided to patients with CKD, no established systems for successful treatment and care exist. Therefore, in this nationwide multicenter cohort study, we analyzed the results of our investigation into the impact of multidisciplinary care systems on CKD patients. Moreover, we investigated the optimal number of healthcare professionals that make up a multidisciplinary care team for maintaining kidney function and improving prognosis.

Methods

The Ethics Committee of Nihon University Itabashi Hospital approved the study (No. RK-220412-10), which was conducted according to the 2015 Ethical Guidelines for Medical and Health Research Involving Human Subjects published by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology and the Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare and Japanese privacy laws. All procedures were performed based on the Helsinki Declaration. The use of de-identified data allowed the requirement for informed consent to be omitted. The registration number of the study in the University Hospital Medical Information Network is UMIN000049995.

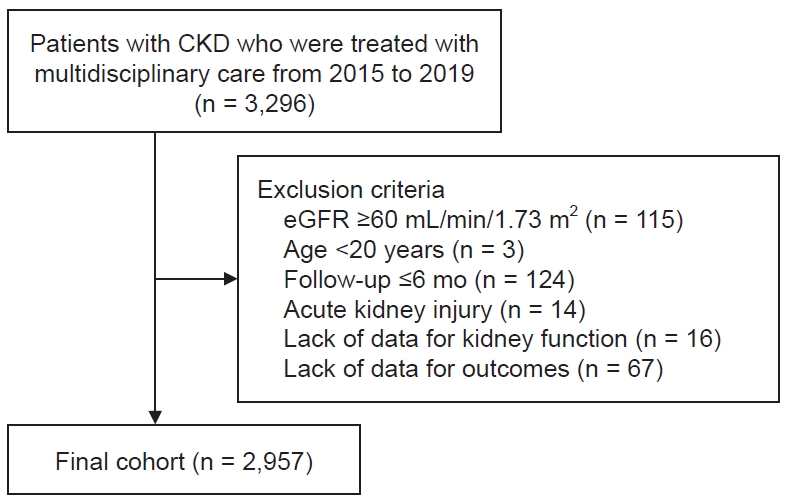

Study design and participants

Approximately 3,000 Japanese patients who were enrolled at 24 chosen medical institutions in Japan, which play a key role in the treatment of CKD patients in each area, were included in this nationwide multicenter study, which was conducted by the committee for the evaluation and dissemination of CKDE in the JKA. The study was intended to reflect the treatment methods used by most Japanese people. A total of 19 tertiary hospitals and five secondary hospitals were included. Patients with CKD who received continuous multidisciplinary care and had data on kidney function available for the 12 months before and the 24 months after receiving multidisciplinary care in Japan were tracked through the end of 2021, and the study period covered January 2015 to December 2019. Patients with CKD who had at least one visit to a nephrologist and were examined by a nephrologist to require more intensive treatment with a multidisciplinary intervention were eligible. The following criteria were used to exclude participants: age younger than 20 years; CKD stages 1 and 2, i.e., ≥60 mL/min/1.73 m

2 for estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR); acute kidney injury; active malignant disease; transplant recipient; history of long-term dialysis; received multidisciplinary care in the past; and missing data on age, sex, or kidney function. According to the number of healthcare professionals on the multidisciplinary care team, the patients were divided into groups A, B, C, and D. The patients in group A were defined as patients who received multidisciplinary medical care from nephrologists and another professional, either nurses or registered dieticians. Patients in group B were defined as patients who received multidisciplinary medical care from three professionals, such as nurses and registered dieticians, besides nephrologists. Patients in group C were defined as patients who received multidisciplinary medical care from four professionals, such as nurses, registered dieticians, and pharmacists, besides nephrologists. Patients in group D were defined as those who received multidisciplinary medical care from five or more professionals, including nurses, registered dieticians, pharmacists, physical therapists, clinical laboratory technicians, and social workers, besides nephrologists. The patients were further separated into two subgroups based on whether they had diabetes or not. The quality of the educational content, which included medical management, dietary recommendations, and lifestyle changes, provided was maintained according to the most recent CKD treatment manual or CKD Teaching Guidebook for CKDEs published by the JKA [

9,

10]. Physical therapists guide exercise therapy to prevent frailty and sarcopenia, according to the Guideline for the Japanese Society of Renal Rehabilitation (JSRR) [

11]. Clinical laboratory technicians explain the target values and significance of kidney-related inspection items to patients with all stages of CKD. Social workers provide patients and families with information on available care services and social resources.

Data collection

The demographic and clinical parameters of the patients, such as their age, sex, history of CVD, primary cause of CKD, and body mass index (BMI), were recorded, as well as hemoglobin, creatinine (Cr), urinary protein, serum albumin, urea nitrogen, eGFR, and glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) for diabetes patients at baseline. CVD was defined as hemorrhagic stroke, limb amputation, coronary artery disease, and ischemic stroke. For Japanese patients, the following formula was used to determine the eGFR: eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m

2) = 194 × serum Cr

−1.094 × age

−0.287 (×0.739 for female) [

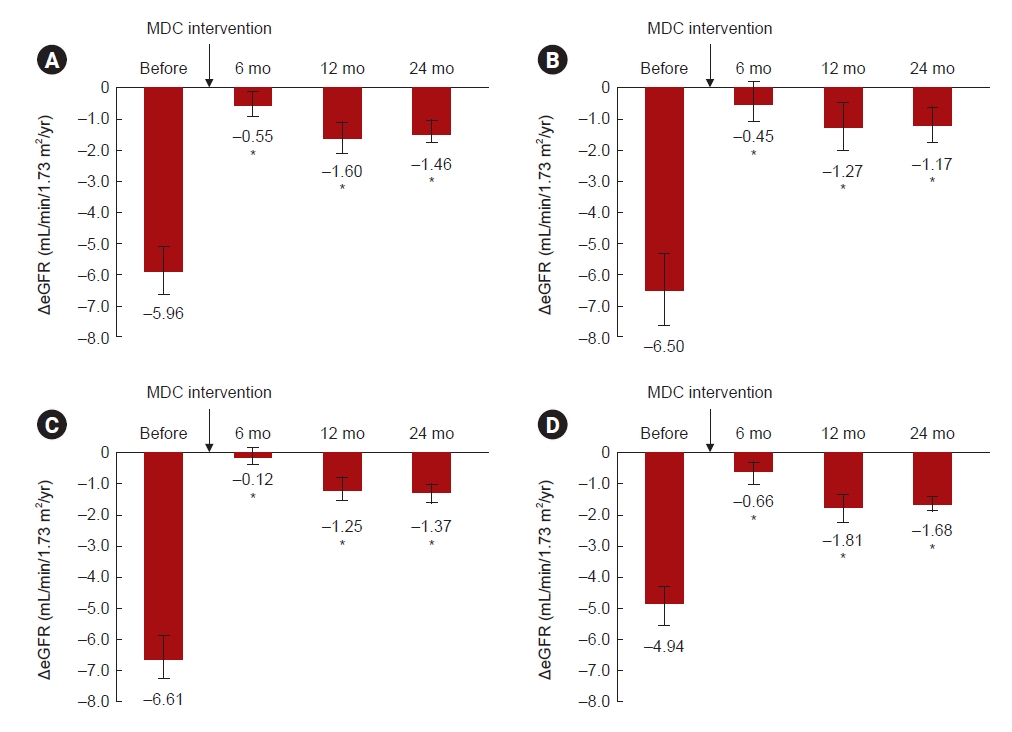

12]. The eGFR values were obtained at 12 months before the intervention by multidisciplinary care and at 6 months, 1 year, and 2 years after the intervention. The annual change in the eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m

2/year) was calculated at each time point of measurement using the following four formulas:

(1) [eGFR (baseline) − eGFR (at 12 months before multidisciplinary care)];

(2) [eGFR (at 6 months after multidisciplinary care) − eGFR (baseline)] × 2;

(3) [eGFR (at 12 months after multidisciplinary care) − eGFR (baseline)]; and

(4) [eGFR (at 24 months after multidisciplinary care) − eGFR (baseline)] × 1/2.

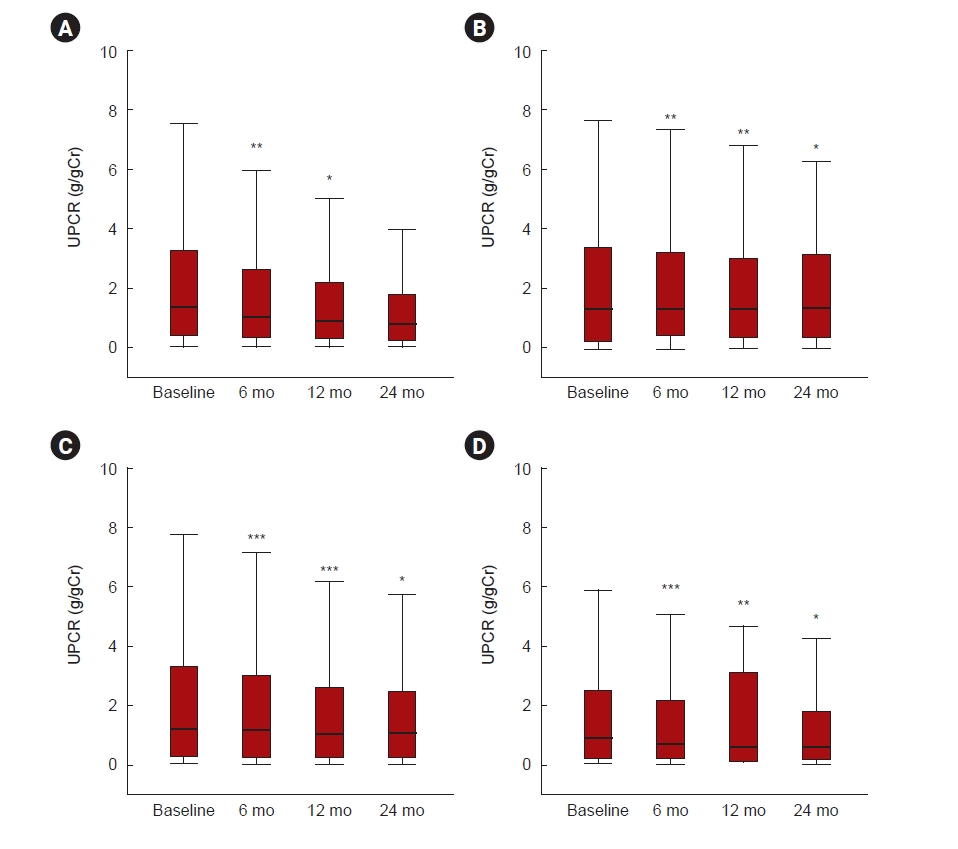

Urinary protein was calculated as the ratio of urinary protein to creatinine (UPCR). The UPCR values were measured at the start of the intervention and at intervals of 6, 12, and 24 months. Method and place of intervention (outpatient or inpatient), number or duration of the intervention (number of visits for intervention for outpatients or hospitalization days for inpatients), and type and number of professionals were collected. The frequency of intervention in outpatient settings, only visits for multidisciplinary care were counted, not every facility visit. Composite outcomes, including dates of all-cause death or the initiation of RRT, were recorded until the composite endpoint was reached or the end of 2021, whichever came earlier. Furthermore, types of RRT, which are hemodialysis, peritoneal dialysis, or kidney transplantation, were recorded.

Statistical analysis

The number and proportion of the data, the mean and standard deviation, or the median (interquartile range [IQR]) are presented. The intragroup comparison was analyzed using two-tailed paired t tests. The chi-squared test was used to analyze categorical variables, and the t test was used to evaluate continuous variables. The repeated-measures analysis of variance was used to compare four groups, with the appropriate use of the Kruskal-Wallis or Tukey’s honestly significant difference tests. The log-rank test was used to evaluate the composite endpoint between groups after the Kaplan-Meier technique was used to estimate it. There were both univariate and multivariate analyses using Cox proportional hazards models adjusted for confounders to examine associations between the number of specialists in multidisciplinary intervention and the composite outcome during 7 years of follow-up. Age, sex, CVD history, and presence or absence of diabetes were considered when calculating the hazard ratios (HRs) using model 1. In addition to the variables in model 1, eGFR and UPCR levels at baseline were considered when calculating the HRs using model 2. In addition to the variables in model 2, model 3 was adjusted for baseline BMI, serum albumin, and hemoglobin levels. Furthermore, based on whether a subject had diabetes or not, subgroup analysis was performed. Additionally, subgroup analysis was performed to evaluate the composite endpoint as per CKD stages at baseline in each group, four groups in each CKD stage at baseline, and according to different intervention settings, i.e., inpatient-based or outpatient-based. HRs with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and p-values are used to express the model results. For the regression analyses, the imputation of missing data was performed using conventional methods, as necessary. JMP version 13.0 (SAS Institute Inc.) was utilized for all analyses. Statistics were deemed significant at a p-value of <0.05.

Discussion

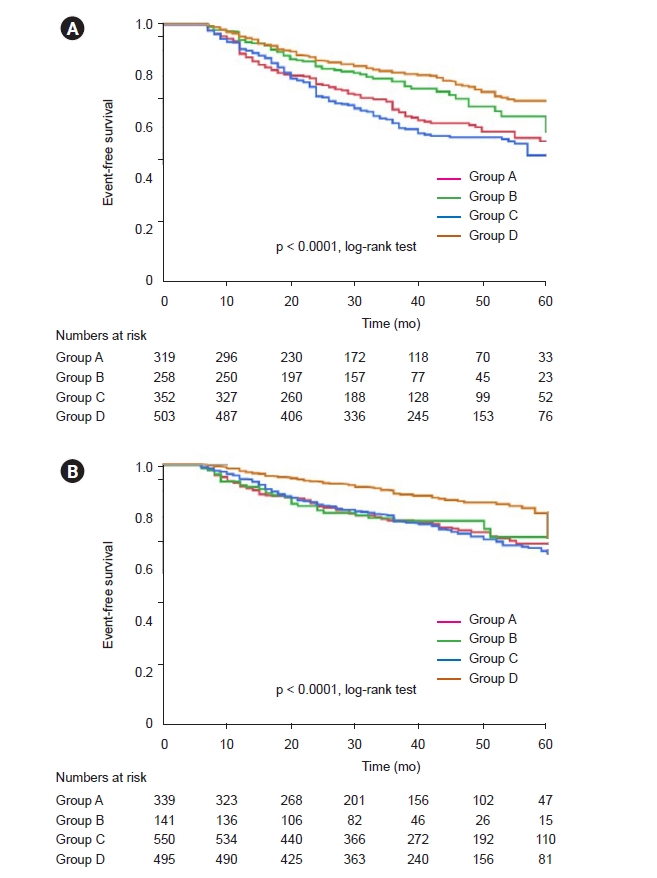

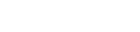

Our nationwide cohort study demonstrated that the multidisciplinary care conducted by nephrologists with at least another specialist could prevent the decline of eGFR and reduce proteinuria levels for 2 years after multidisciplinary care. Furthermore, the multifactorial intervention provided by a team comprised of five or more professionals, including nephrologists, has been shown to improve patient outcomes for 7 years. The present study included 2,957 individuals from 24 facilities in Japan; therefore, the large sample size drawn from a multicenter study is one of its main advantages, along with the relatively long observation and the inclusion of a comparatively high number of elderly patients. This study is the first to indicate that a multidisciplinary care team with five or more professionals may be able to prevent initiating RRT and reduce all-cause mortality regardless of whether the CKD patients have diabetes or not. A multidisciplinary care team should include a nephrologist and other professionals from other fields and is recommended for those with stages 3 to 5 of CKD.

The mean annual decline of eGFR before multidisciplinary care was −5.9 mL/min/1.73 m

2 in this study. It has been reported that when the eGFR falls below 45 mL/min/1.73 m

2, it declines at a rate of −9.9 mL/min/1.73 m

2/year in diabetic nephropathy and −4.8 mL/min/1.73 m

2/year in hypertensive nephropathy until the initiation of dialysis in Japanese CKD patients [

13]. Furthermore, the annual decline rate of eGFR from 45 mL/min/1.73 m

2 to dialysis initiation was greater than the decline rate of eGFR from 60 mL/min/1.73 m

2 to 45 mL/min/1.73 m

2 [

13]. Therefore, annual decline of eGFR was higher in the present study because the mean eGFR levels at baseline was 25.8 ± 12.5 mL/min/1.73 m

2. According to reports, poor drug adherence has been linked to problems, CKD progression, unplanned hospitalization, higher medical expenses, early impairment, and mortality [

14,

15]. Across disease states, treatment protocols, and age groups, men have relatively high discontinuous visit rates; the first few months of treatment are when this rate is highest [

16]. Most patients with CKD, particularly those in stage 3, are asymptomatic, and interruption of visits is one of their significant issues. Reportedly, multidisciplinary care improves adherence to management targets given in CKD guidelines, and this adherence leads to an enhanced renal prognosis even in patients with CKD stage G3 [

17]. Collaborative integration by multidisciplinary care professionals is critical in helping patients modify their lifestyles and efficiently achieve treatment goals established by guidelines [

18]. Although the present study included 2,957 patients, only 2% of follow-up on some patients was lost. However, we could not evaluate whether the multidisciplinary care in this study was able to successfully achieve behavioral modification, improve patient compliance and adherence, and reduce the discontinuation rate of outpatient visits. Nevertheless, we believe that multidisciplinary care may be associated with improved patient health literacy and the prevention of worsening kidney function.

Nephrologists, dieticians, nurses, pharmacists, and social workers generally make up the multidisciplinary care team for patients with CKD, and each of them is crucial to the management of these patients [

8]. However, the present study found that the composition of professionals in the multidisciplinary care team varied significantly by institution and intervention method. Regarding intervention methods, multidisciplinary care teams consisting of two or three professionals, including nephrologists, were primarily delivered in outpatient settings, whereas teams of four or more professionals were delivered in the inpatient setting. Inpatient multidisciplinary care programs for patients with CKD have not been implemented extensively in Western countries, probably reflecting differences in the medical insurance system between Japan and Western countries. Although multidisciplinary care provided in an outpatient setting is reimbursed for patients with diabetic kidney disease in Japan, it is not reimbursed for patients with other etiologies of CKD. However, full reimbursement is available for these patients if they are admitted to hospital. Accordingly, interventions by pharmacists and physical therapists are possible in the inpatient setting. Moreover, regarding the number of healthcare professionals consisting of multidisciplinary care teams, registered dieticians are the most common, followed by specific nurses, pharmacists, physical therapists, and the number of physical therapists is greater than that of social workers in Japan. As per recent studies, kidney function is linked to physical activity in people with CKD, and increasing physical activity levels may slow the decline of kidney function [

19–

22]. There is a guideline for exercise therapy for patients with predialysis CKD and dialysis from the JSRR [

11]. Consequently, physical therapists, preferably with CKD knowledge, were widely used to treat CKD patients in Japan, and they must be considered members of multidisciplinary care teams. Our results showed that the most physical therapists were included in group D. Therefore, further investigation would be needed since the physical therapists might be a key player in improving the prognosis of patients with CKD. According to a meta-analysis, CKD patients receiving multidisciplinary care had a considerably lower chance of dying from any cause than those who were not receiving it [

23]. However, when nephrologists and nurses made up the multidisciplinary care teams, there was no significant difference in all-cause mortality between the multidisciplinary and non-multidisciplinary care groups. Furthermore, it has been hypothesized that the all-cause death rate for CKD patients would decrease when the multidisciplinary care team included not just nephrologists and nurses but also experts from other specialties. A multidisciplinary care team that only includes nephrologists and nurses might not be the best choice for improving outcomes for CKD patients according to a meta-analysis [

23]. The present study found that the intervention of at least one professional besides nephrologists can prevent the decline of kidney function in CKD patients more than nephrologists alone. Moreover, the present study revealed that a multidisciplinary care team consisting of five or more healthcare professionals could provide the best outcomes, regardless of any underlying CKD disease. However, further investigations are needed to determine which professionals and how many staff members comprise multidisciplinary care teams that achieve the best outcomes.

A self-management program’s overarching objective is to empower and enable people to advance their knowledge and abilities in self-management [

24]. Therefore, it helps diabetes patients lower their risk of developing long-term microvascular and macrovascular problems, severe hypoglycemia, and diabetic ketoacidosis. Besides maximizing patient well-being, self-management programs seek to enhance the quality of life and achieve treatment satisfaction [

25]. Patients with diabetes are frequently given lifestyle management services, such as medical nutrition therapy, physical exercise, weight loss counseling, smoking cessation counseling, and emotional support. Fundamental components of diabetes care include self-management training and assistance. According to reports, patients with diabetes who participate in a program with a planned, patient-centered curriculum and more than 10 hours of contact time each week have the best results [

26]. Self-management education, according to the American Diabetes Association, is a continuous process that encourages the information, skills, and competencies required for diabetes self-care. It also combines a patient-centered approach and collaborative decision making [

27]. A multidisciplinary care team should deliver the program either one on one or in groups, with support available over the phone or online, according to the National Clinical Institute for Care and Excellence in the United Kingdom. This team should include at least one trained or accredited healthcare professional, such as a registered dietitian or diabetes specialist nurse [

28]. A structured self-management education program should be implemented for individuals with diabetes and CKD, according to the KDIGO (Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcome) clinical practice guideline for 2022 [

29]. To provide complete treatment for patients with diabetes and CKD, policymakers and institutional decision makers promote team-based, integrated care with a focus on risk assessment and patient empowerment. Multiple factors related to lifestyle, including diet, exercise, and psychosocial factors, can influence medication noncompliance and worsen outcomes [

30–

32]. The present study suggested that multidisciplinary care was effective not only in diabetes patients with CKD but even in patients without diabetes but with CKD. Therefore, team-based, integrated care programs based on the structured and patient-centered curriculum should be established, and further preparation and dissemination of multidisciplinary team-based care are required for all CKD patients.

The current study has some limitations. First, we could not investigate blood pressure, body weight, laboratory findings other than kidney function, or medications, which were other unknown confounding factors. Salt restriction through multidisciplinary intervention may have lowered blood pressure, reduced proteinuria, and maintained kidney function. The patients with diabetes in group C had poor prognoses, and HbA1c level was considerably higher. Therefore, patients with higher risk factors that could not be measured or collected in this study might be included. In addition, group B had higher event rate despite ΔeGFR in group B was lower compared to group D. However, group B had higher UPCR levels through 2 years. Reduction of UPCR by multidisciplinary care might be associated with improvement of prognosis, therefore, further study should be required. Although it has been reported that an early referral to a nephrologist is more useful than a late referral, we could not collect the times and duration of management for nephrologists before multidisciplinary care. We were unable to adequately investigate the important factors involved in maintaining kidney function among the four groups. Second, the current study was excluded from a non-multidisciplinary control group. In cohort studies, multidisciplinary treatment was linked to decreased all-cause mortality, but this was not demonstrated in the randomized control trials for patients with CKD [

23]. Therefore, additional prospective randomized controlled trials for patients with CKD are required to validate the efficacy of multidisciplinary therapy. Finally, there may have been some degree of patient selection and facility bias. Bias in the facility and patient selection may have existed to some extent. Although the number of professionals on the multidisciplinary care team did not vary by hospital size, it depended on the functions of each hospital, such as the type and number of healthcare professionals available. The content of the education program, the systems delivered, and the makeup of the patient population varied as per each facility. Further studies are needed to clarify whether multiple education sessions by the same personnel or one session by each personnel is superior to multidisciplinary care in an inpatient setting. Additionally, the role of each professional is not clearly defined. Programs for self-management and education that include content, assessments of duration, contact frequency, and delivery techniques should be established.

In conclusion, a multidisciplinary care team comprised of five or more professionals may be linked to a better prognosis for kidney disease and overall mortality. Furthermore, multidisciplinary team-based treatment is expected to be effective for CKD other than diabetes. To manage patients holistically, multidisciplinary care integrates several professionals and is patient-centered. A multidisciplinary care team should be delivered by nephrologists and other professionals, not only CKDEs such as trained nurses, dieticians, and pharmacists but also physical therapists and social workers, ideally with an understanding of CKD.

PDF Links

PDF Links PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link Full text via DOI

Full text via DOI Download Citation

Download Citation Supplement table 1

Supplement table 1 Print

Print