NADPH oxidase inhibitor development for diabetic nephropathy through water tank model

Article information

Abstract

Oxidative stress can cause generation of uncontrolled reactive oxygen species (ROS) and lead to cytotoxic damage to cells and tissues. Recently, it has been shown that transient ROS generation can serve as a secondary messenger in receptor-mediated cell signaling. Although excessive levels of ROS are harmful, moderated levels of ROS are essential for normal physiological function. Therefore, regulating cellular ROS levels should be an important concept for development of novel therapeutics for treating diseases. The overexpression and hyperactivation of NADPH oxidase (Nox) can induce high levels of ROS, which are strongly associated with diabetic nephropathy. This review discusses the theoretical basis for development of the Nox inhibitor as a regulator of ROS homeostasis to provide emerging therapeutic opportunities for diabetic nephropathy.

Two faces of reactive oxygen species

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) encompassing superoxide anion (O2.–), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), and hydroxyl radical (OH.) are believed to be simple by-products of aerobic respiration [1–3]. Uncontrolled and high concentrations of ROS result in oxidative stress that can lead to peroxidation of lipids, oxidation of proteins and nucleic acids, and ultimately cause cellular damage [1–3]. Therefore, ROS production should be tightly regulated during physiological events. A growing body of evidence has indicated that ROS can serve as secondary messengers in signaling transduction pathways mediated by various agonists such as growth factors, hormones, and cytokines to regulate cell growth, apoptosis, and differentiation [1–5]. It has been well established that phosphotyrosine of cellular proteins plays an essential role in cellular proliferation [6–9]. Stimulation of growth factor can result in increased tyrosine phosphorylation, leading to cell proliferation. Tyrosine phosphorylation is regulated by a balance between protein tyrosine kinase (PTK) and protein tyrosine phosphatase (PTPase). The PTPase family contains the conserved sequence Cys-X-X-X-X-X-Arg (Cys-X5-Arg, X indicates any amino acid) in an active center. Conserved cysteine residue in the active center possesses a low pKa through the positive charge of arginine residue and exists as a thiolate anion (-S–), which is easily oxidized by H2O2. Oxidation of thiolate anion in PTPase is converted to sulfenic acid (-SOH), which can then induce the loss of phosphatase activity of PTPase. Oxidation of PTPase can disrupt the balance between PTK and PTPase. PTK activity is then relatively enhanced, resulting in increased tyrosine phosphorylation of target cell signaling-related proteins and cell proliferation [8,9].

Reactive oxygen species generation from mitochondrial respiratory chains

It is known that sources of ROS include the electron transport chain (ETC) in mitochondria and metabolic enzymes such as glucose oxidase, xanthine oxidase, cytochrome p450, and NADPH oxidase (Nox) [1–5,10–12]. This suggests that different complexes of cellular events are involved in ROS generation. Metabolic enzymes including cytochrome p450, glucose oxidase, and xanthine oxidase can produce a constant level of ROS generation, indicating that the ROS generation was not correlated with the pathogenesis of diabetic nephropathy (DN). In contrast to metabolic enzyme-generated ROS, mitochondrial ROS are known to account for a large proportion of total cellular ROS [13–15]. The ETC complexes are located in the mitochondrial inner membrane (respiratory complexes I–IV). Electron leakage from the mitochondrial ETC can generate superoxide, which is converted into H2O2 by manganese superoxide dismutase (Mn-SOD) in the mitochondrial matrix [16,17]. It has been reported that complex I and complex III of the mitochondrial ETC are major sites for ROS generation. However, kidney tissues in hyperglycemia can exhibit reduced expression of complex I and complex III of the ETC. An impaired ETC complex in diabetic conditions results in leaked electrons, leading to ROS generation. Many reports have indicated that mitochondrial Mn-SOD expression is decreased in DN. Reduction of mitochondrial Mn-SOD expression can induce the level of mitochondrial superoxide [18]. However, other reports have suggested that Mn-SOD deficiency fails to induce diabetic kidney diseases [19]. More detailed molecular studies between increased mitochondrial ROS and DN must be performed.

Regulation of NADPH oxidase activation

Nox is known to contribute to ROS generation in response to various agonists. Since the first discovery of gp91phox/Nox2 in phagocytic cells, an additional six homologues of Nox2 (Nox1, Nox3, Nox4, Nox5, dual oxidase 1 [Duox1], and dual oxidase 2 [Duox2]) have been identified in various nonphagocytic cells [4,5,12,20,21]. All seven Nox isozymes are composed of a single polypeptide. They can be divided into three types based on functional domain: 1) six transmembrane α-helical domains containing tandem heme group homologues to ferric reductase in the NH2-terminal region; 2) flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD)-binding site in the membrane proximal region; and 3) NADPH-binding site homologues to ferredoxin-NADP+ reductase in the long COOH-terminal region. Electrons from NADPH are transferred to oxygen molecules through FAD and two hemes, leading to the generation of O2.– and H2O2. Activations of Nox isozymes are regulated by unique regulatory mechanisms [4,5,22]. The Nox2 protein is required for one integral protein p22phox; three cytosolic proteins p47phox, p40phox, and p67phox; and small G-protein Rac (Fig. 1A). The p47phox serves as a core protein in the complex. The tandem Src homology 3 (SH3) domains of p47phox can interact with the proline-rich region (PRR) in the COOH-terminal region of the p22phox protein, leading to membrane targeting. Meanwhile, the PRR in the COOH-terminal region of p47phox can recruit the SH3 domain of p67phox. Four tetratricopeptide repeats in the NH3 terminal region of p67phox protein provide the binding site for G-protein Rac. The phox and bem1 (PB1) domain between the two SH3 domains of the p67phox protein serves as the site for the molecular interaction of p67phox protein with the PB1 domain of p40phox. Interactions among an integral protein p22phox; three cytosolic proteins p47phox, p40phox, and p67phox; and Rac provide a stable protein complex of Nox2 to allow electron transfer from NADPH to O2 (Fig. 1A).

Structure and activation of Nox isozymes [22].

Regulation of Nox isozymes. (A) Nox2-p22phox dimer associates with p47phox, p67phox, p40phox, and Rac. (B) Nox1-p22phox complex also binds to NoxO1, NoxA1, and Rac. (C) Nox4-p22phox interacts with SH3YL1 for activation. (D and E) The EF hand motif of the N-terminus region in Nox5 and Duox1/2 isozymes binds to intracellular calcium for their activation.

Duox, dual oxidase; FAD, flavin adenine dinucleotide; Nox, NADPH oxidase; PRR, proline-rich region.

Nox1 proteins need to form a complex with integral protein p22phox and two cytosolic proteins Nox organizer 1 (NoxO1) as the homologue of p47phox, Nox activator 1 (NoxA1) as the homologue of p67phox, and small G-protein Rac (Fig. 1B). The activation pattern of Nox1 is similar to that of Nox2. The PRR of p22phox with the SH3 domain of NoxO1 can interact with the SH3 of the NoxO1 protein serving as a central scaffolding molecule in Nox1 complex formation. The PRR of NoxO1 provides a binding site for the SH3 domain of the NoxA1 protein, which contains four tetratricopeptide repeat domains in the NH2-terminal region for Rac binding sites [23]. Nox5 and Duox1/2 contain a Ca2+-binding EF hand domain in the NH3-terminus region, which provides an intracellular calcium binding site resulting in their activation (Fig. 1D, E). These isozymes do not require integral or cytosolic proteins.

Since Nox4 has been identified from the kidney, many reports have indicated that Nox4 activation is associated with chronic kidney disease. In contrast to other Nox isozymes, the molecular mechanism of Nox4 activation has remained unclear other than that it requires the integral protein p22phox (Fig. 1C). Although polymerase delta-interacting proteins2 (Poldip2) has been identified as a cytosolic activator for Nox4, the molecular mechanism for the interaction between Nox4-p22phox and Poldip2 has not been suggested [24]. Recently, Yoo et al. [25] reported that the Ysc84p/Lsb4p, Lsb3p, and plant FYVE proteins region in the NH3 terminal region and the SH3 domain in the COOH-terminal region of SH3YL1 can interact with the Nox4-p22phox complex to result in Nox4-dependent H2O2 generation (Fig. 1C). It has been demonstrated that formation of a ternary complex of p22phox-SH3YL1-Nox4 leading to H2O2 generation induces severe renal failure in a lipopolysaccharide-induced acute kidney injury model. However, the regulatory mechanism by which high glucose or transforming growth factor β1 regulates the ternary complex of p22phox-SH3YL1-Nox4 formation in fibrosis and DN remains to be determined.

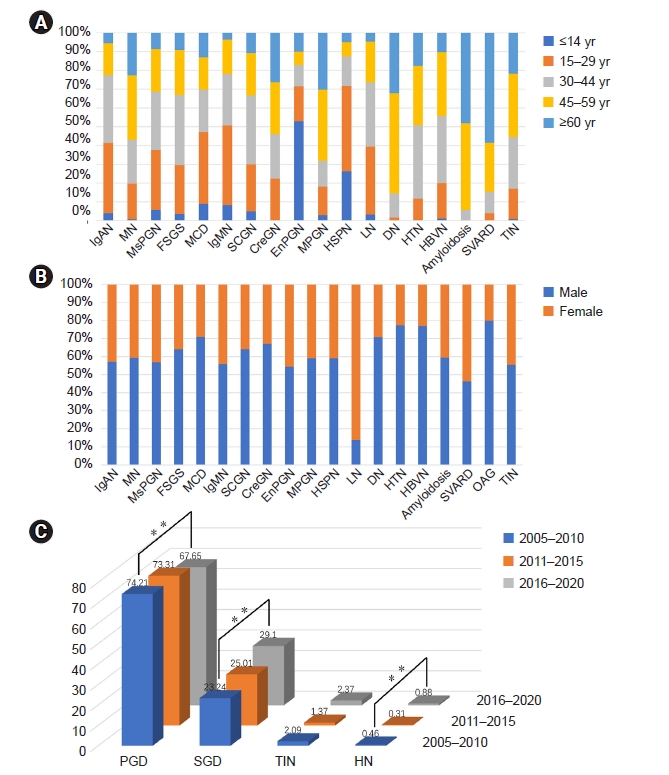

Uncontrolled reactive oxygen species generation is associated with diabetic nephropathy: water tank model

A water tank has an inlet and outlet. If the amount of water entering from the inlet and exiting to the outlet is constant, a certain amount of water will always remain in the water tank (Fig. 2). ROS homeostasis including ROS generation and elimination exhibits a similar pattern to the water tank model. ROS can be generated from various cellular sources including Nox activation and mitochondrial respiratory chains, whereas ROS elimination is mediated by the action of cellular antioxidants (glutathione, uric acid, ascorbic acid [vitamin C], α-tocopherol [vitamin E], and ubiquinol [coenzyme Q]) and antioxidant enzymes (SOD, catalase, glutathione S-transferase, and peroxiredoxin) [26–30]. In a normal physiological condition, a balance between ROS generation and elimination is well regulated, and a certain amount of remaining ROS serves as secondary messengers in cell signaling. In a pathological stage, Nox isozymes and their regulating proteins are overexpressed, resulting in uncontrolled ROS generation [31–34]. As the balance of ROS homeostasis is disrupted, the level of ROS is gradually increased in the body, which is closely associated with the pathogenesis of DN [35–37]. Therefore, uncontrolled Nox activation should be suppressed by treatment with Nox inhibitor as an emerging therapy for DN (Fig. 2).

Water tank model for ROS homeostasis.

ROS homeostasis including ROS generation and elimination has a similar pattern to the water tank model, which has a water inlet and outlet. Over-activation of Nox isozymes leads to uncontrolled ROS generation that can disrupt the balance of ROS homeostasis. Nox activation should be suppressed by treatment with Nox inhibitors as an emerging therapy for diabetic nephropathy.

Nox, NADPH oxidase; ROS, reactive oxygen species.

Since uncontrolled ROS generation is involved in DN, many studies on antioxidant therapies for DN have been conducted [38,39]. Thirteen independent clinical studies have shown inconsistent results, strongly indicating that the beneficial effects of antioxidants on DN progression are controversial [40–52]. Why are there so many inconclusive trials on antioxidant therapy? Several points in the clinical studies must be considered. The first point is that the supplement of antioxidants might not be enough to eliminate ROS present in the disease (Fig. 3). Since antioxidants can be distributed to the entire body, they cannot pinpoint pathogenic tissues to eliminate uncontrolled ROS. Therefore, antioxidant therapy is not sufficient for treating chronic kidney disease [38,39]. The second point is that the function of the antioxidant might be nonspecific for scavenging ROS in the entire body. This indicates that nonspecific antioxidants might eliminate appropriate ROS that could potentially play a role in the normal physiology of the human body. In contrast to antioxidants, Nox inhibitors might specifically regulate uncontrolled ROS inlets, resulting in decreasing ROS levels in the entire body to support the return of normal ROS balance (Fig. 3).

Antioxidant therapies for chronic kidney disease.

Many clinical studies have shown that the beneficial effects of antioxidants on chronic kidney disease progression are controversial. Antioxidants are insufficient for removing excessive ROS. However, Nox inhibitors can control ROS levels to support return to normal ROS balance.

ROS, reactive oxygen species.

Oxidative stress in diabetic nephropathy

DN is one of the complications of diabetes and is the leading cause of renal failure resulting in end-stage renal disease [53–55]. In the early stages of DN, increasing albuminuria secretion and reduction of the glomerular filtration rate are common. Glomerular basement membrane thickening, mesangial expansion, overexpression of extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins, tubulointerstitial fibrosis, and glomerulosclerosis can contribute to the progression of DN [56–58]. Several lines of evidence suggest that oxidative stress mediated by uncontrolled ROS generation is associated with the pathogenesis of DN [37,53]. Renal oxidative stress is involved in the activation or overexpression of various Nox isozymes [37]. Previous reports have indicated that various Nox isozymes and their accessory proteins such as p22phox, p47phox, and p67phox are expressed in kidney tissues [22]. Mesangial cells express Nox1, Nox2, and Nox4. Podocytes contain Nox2, Nox4, and Nox5. The upregulation of Nox4 and Nox5 plays a role in mesangial cell hypertrophy, tissue expansion, ECM protein accumulation, and apoptosis of podocytes [37]. Blood vessels in kidney tissues are composed of vascular smooth muscle cells and endothelial cells expressing Nox1, Nox4, and Nox5 known to be responsible for ROS generation in response to angiotensin Ⅱ [59]. Proximal tubule cells express Nox1, Nox4, and Nox5 isozymes [34,60,61]. Most Nox isozymes are expressed in different kidney tissues and cells [34]. Nox4 is predominantly expressed in all kidney cells [62–65]. Its expression is upregulated in diabetic conditions. Deletion of Nox4 can attenuate mesangial hypertrophy and ECM accumulation in diabetic conditions [66]. Moreover, inflammatory cytokine production and macrophage infiltration are reduced in Nox4 KO mice [31,67]. In contrast to Nox4, the function of Nox1 and Nox2 in DN is controversial [31,68,69]. Although Nox1 is associated with ROS generation and renal oxidation in diabetic conditions, the molecular function of Nox1 in the pathogenesis of DN remains unclear.

Development of Nox inhibitors for treatment of diabetic nephropathy

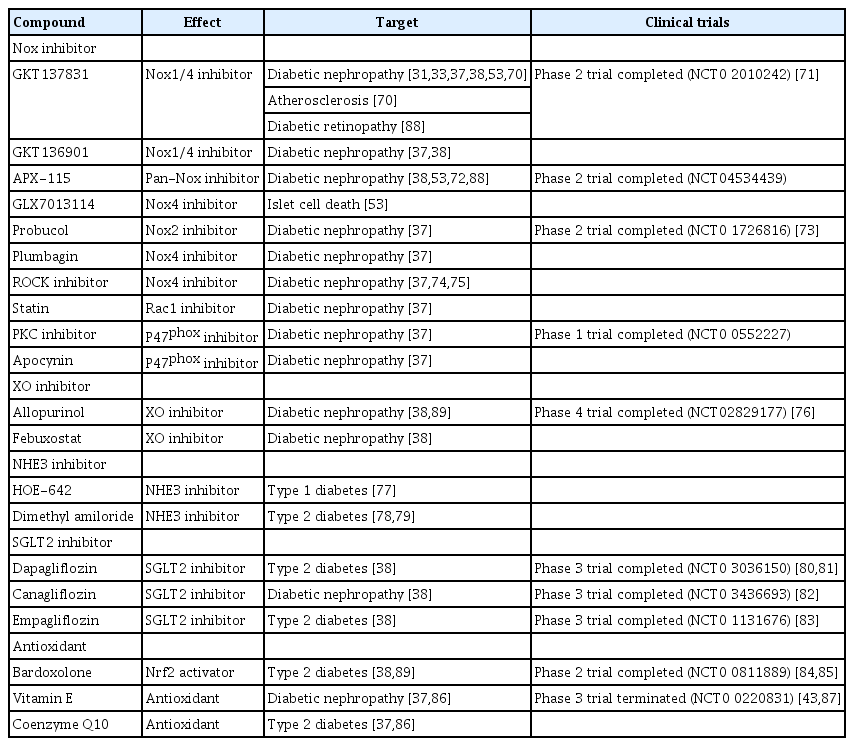

Many studies have demonstrated that oxidative stress plays an important role in DN. Therefore, various clinical trials for therapeutic agents regulating oxidative stress are continuously being conducted (Table 1) [70–89]. Although no effective therapy exists for treatment of DN, clinical trials for therapeutic Nox inhibitors are ongoing [88,89]. A dual Nox1/4 inhibitor GKT137831 (brand name: Setanaxib), a pyrazolopyridine compound, was developed by Genkyotexn (Stockholm, Sweden) [90]. In streptozotocin-induced diabetic ApoE–/– mice, GKT137831 attenuated diabetic-induced glomerular damage including ECM accumulation and glomerular structural changes [31]. Moreover, it has been reported that GKT137831 regulates the reduction of mesangial matrix expansion and podocyte loss in a type Ⅰ diabetes model [33]. GKT137831 is now enrolled in a phase 2 clinical trial for type Ⅰ DN in Australia. The Ewha-18278 compound was first developed for osteoporosis treatment by Joo et al. [91]. The compound was transferred to AptaBio Corp. (Suwon, Korea) and is now referred to as APX-115 (Table 1). In db/db mice as a type II diabetes model, APX-115 suppressed mesangial expansion and urinary albumin excretion [72]. Renal Nox5 expression was highly increased in renal podocyte-specific Nox5 transgenic mice (Nox5 pod+). Moreover, APX-115 inhibited Nox5 expression and levels of urinary albumin and creatinine in Nox5 pod+ mice, indicating APX-115 as a potentially therapeutic agent for treatment of DN through inhibition of macrophage infiltration to the glomerulus, a renal inflammatory signal related to tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor and Nox5 expression. APX-115 is now in a phase 2 clinical trial for DN in the European Union. Rho-associated coiled-coil-containing protein kinase (ROCK) and sodium glucose cotransporter (SGLT) 2 are novel treatments for DN [74,75]. Fasudil, a ROCK inhibitor, reduced albuminuria in db/db mice. Canagliflozin, an SGLT inhibitor, is a compound under development by Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma Corp. and has completed phase Ⅲ clinical trials in Japan. The novel compound improved renal outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes [82]. Xanthine oxidase inhibitors and antioxidants regulating oxidative stress are summarized in Table 1.

Conclusion

Homeostasis between ROS generation and elimination plays an important role in normal physiological functions. Uncontrolled ROS generation through over-activation of Nox activity is closely associated with the pathogenesis of DN. Uncontrolled Nox activation should be suppressed by treatment with Nox inhibitors as an emerging therapy for DN. Recently, two Nox inhibitors (GKT137831 from Genkyotex and APX-115 from AptaBio) have been subjected to clinical phase II trials for DN patients. We believe that these Nox inhibitors provide new hope for DN patients.

Notes

Conflicts of interest

All authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding

This work was supported by the Aging project (2017M3A9D8062955 to YSB) and Bio-SPC (2018M3A9G1075771 to YSB) funded by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) and Ministry of Science and ICT, and by a grant from the Korea Health Technology R&D Project (HI21C0293 to HEL) through the Korea Health Industry Development Institute (KHIDI), funded by the Ministry of Health & Welfare.

Authors’ contributions

Conceptualization: YSC, YSB

Writing–original draft: YSC, YSB

Writing–review & editing: All authors

All authors read and approved the final manuscript.