Prostaglandin E2 receptors as therapeutic targets in renal fibrosis

Article information

Abstract

Prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), a lipid mediator produced by the cyclooxygenase enzyme system, is the main prostaglandin in the kidney. PGE2 is involved in various physiological and pathophysiological processes in the kidney, including renal hemodynamics, water and salt balance, and renal fibrosis—a key pathological feature of progressive kidney diseases. PGE2 functions by binding to four G-protein-coupled EP receptors (EP1 to EP4), which stimulate different intracellular signaling pathways. The intrarenal distribution of the four EP receptors as well as the different downstream signaling pathways associated with each receptor give rise to the distinct functional consequence of activating each receptor subtype. This review summarizes the current data on the renal expression of the four EP receptors and delineates the role of each receptor in renal fibrosis.

Introduction

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) affects 8% to 16% of the global population and is the 16th leading cause of years of life lost. CKD incidence and prevalence have been increasing concurrently with increases in lifespan and lifestyle diseases such as diabetes, hypertension, and obesity [1,2]. CKD is defined by the presence of kidney abnormalities, a decline in renal function (glomerular filtration rate [GFR] of <60 mL/min/1.73 m2), or albuminuria for more than 3 months [3]. CKD is characterized by the development of renal fibrosis and progressive loss of renal function, and ultimately CKD leads to end-stage renal disease (ESRD). The main goal of CKD therapy is to hamper progression to ESRD by treating underlying diseases, such as hypertension, diabetes, and albuminuria, and to prevent cardiovascular disease, which is the main cause of morbidity and mortality in CKD patients [4]. However, despite these therapeutic approaches, the absolute risk of renal and cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in the CKD population remains extremely high [5]. Therefore, more effective therapeutic options are needed to effectively halt the progression of renal function loss.

Regardless of the primary cause, renal fibrosis is the hallmark of progressive CKD. Fibrosis is characterized by excessive deposition of extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins by activated myofibroblasts, resulting in loss of organ architecture (scarring) and function [6,7]. Fibrogenesis is initiated in response to chronic kidney damage; following renal injury, profibrotic factors are produced by injured tubular epithelial cells and infiltrating inflammatory cells that stimulate signaling events leading to myofibroblast activation and ECM production [8,9].

Transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) is one of the key regulators involved in the fibrotic process and, irrespective of etiology, elevated TGF-β levels correlate with increased activity of profibrotic signaling pathways and CKD progression [10,11]. TGF-β can directly promote ECM protein production, including collagen 1 and fibronectin, via the Smad signaling pathway, which is recognized as a major pathway of TGF-β signaling in progressive renal fibrosis [10,12]. Moreover, several studies have demonstrated that TGF-β stimulates expression of cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) and the production of its metabolic product prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) in renal cells [13–18], indicating an important role for the COX-2/PGE2 system in renal fibrosis and CKD. The focus of this review is the role of PGE2 in the development and progression of renal fibrosis in CKD. We will particularly highlight PGE2 EP receptors as promising targets for renal fibrosis.

The prostaglandin system

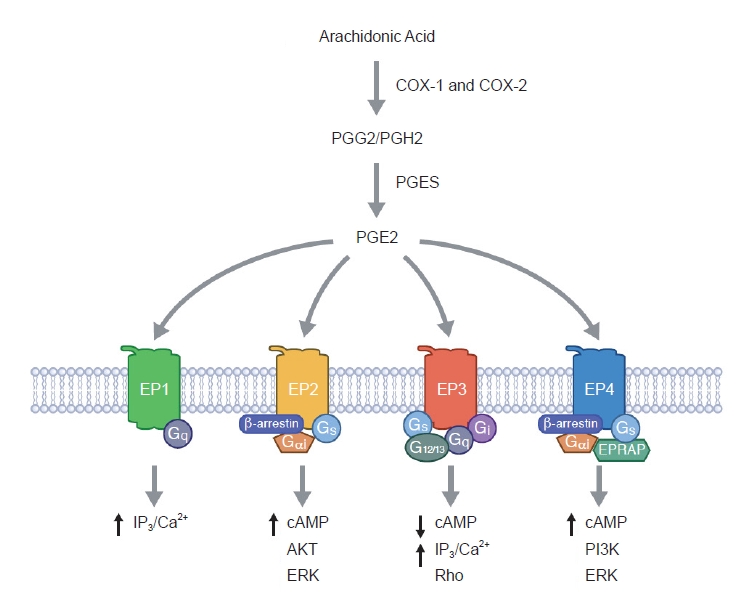

Prostaglandins are important lipid mediators that play critical roles in modulating numerous physiological and pathophysiological actions in different organs. In the kidney, prostaglandins are of major importance for regulating renal hemodynamics, like mediating blood pressure and fluid metabolism [19–21]. Similarly, prostaglandin synthesis can be stimulated in response to different pathophysiological situations, including inflammation, pain, and cancer [22,23]. Prostaglandins are derived from arachidonic acid and are metabolized to the intermediary product prostaglandin G2/prostaglandin H2 (PGG2/PGH2), which is further converted to the bioactive PGE2, prostaglandin I2 (PGI2), prostaglandin D2 (PGD2), prostaglandin F2α (PGF2α), and thromboxane A2 (TXA2) by tissue-specific synthases [24]. These prostaglandins primarily exert their function by binding to specific prostaglandin receptors, with each prostaglandin modulating different cellular biochemical pathways depending on the specific receptor stimulated [25–27]. COX chiefly regulates the production of the five abovementioned prostaglandins by adjusting the substrate (PGG2/PGH2) supply to the individual tissue-specific synthases. The COX enzyme exists in two isoforms; COX-1 and COX-2. We have previously provided an exhaustive review of the role of the COX enzymes in several physiological and pathophysiological processes in the kidney [28].

Prostaglandin E2

PGE2 is the major prostaglandin in the kidney and the role of PGE2 in renal health and disease has been widely studied. PGE2 can be produced by all renal cells via the enzyme PGE2 synthase. Currently, three PGE2 synthases have been cloned, including microsomal prostaglandin E2 synthase (mPGES)-1, mPGES-2, and cytosolic PGES [29]. Among the three PGES isoforms, mPGES-1 has been identified as the most abundant renal PGES. It is highly inducible in response to (patho)physiological stimuli and acts in concert with COX-2 to generate PGE2 [29–31]. The role of mPGES-1 in CKD is complex [32]. In a paper by Jia et al. [33], it was demonstrated that inhibition of mPGES-1 may be a novel therapeutic strategy for improving renal function and urine concentration ability in an experimental model of CKD.

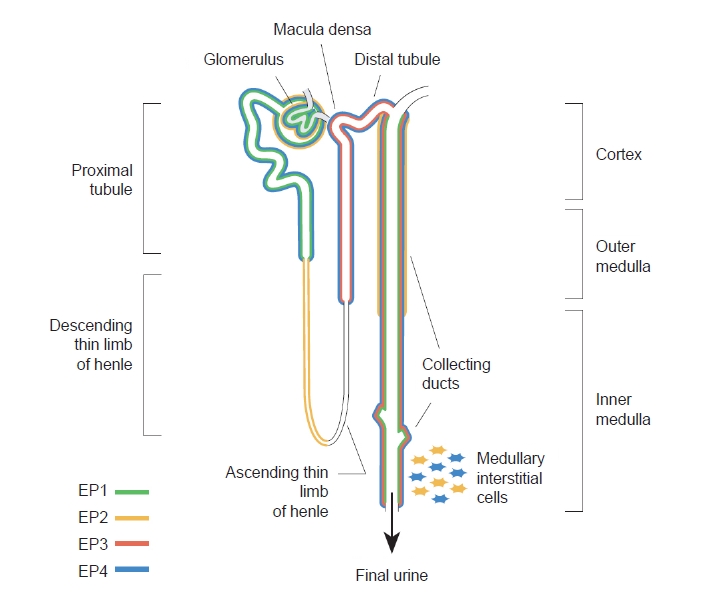

PGE2 can bind to four G-protein-coupled EP receptors (EP1–EP4) that stimulate different intracellular signaling pathways [25–27,34,35]. The COX pathway leading to PGE2 synthesis as well as its downstream receptors are depicted in Fig. 1. These EP receptors are often simultaneously expressed in renal cells and their relative expression levels dictate the overall cellular response to PGE2. The localization of the EP receptors along the nephron is illustrated in Fig. 2.

The cyclooxygenase enzyme system and prostaglandin E2 signaling pathways.

cAMP, cyclic adenosine monophosphate; COX, cyclooxygenase; EPRAP, EP4 receptor-associated protein; ERK, extracellular signal-regulated kinase; IP3, inositol trisphosphate; PGES, prostaglandin E synthase; PGE2, prostaglandin E2; PGG2, prostaglandin G2; PGH2, prostaglandin H2; PI3K, phosphoinositide 3-kinase.

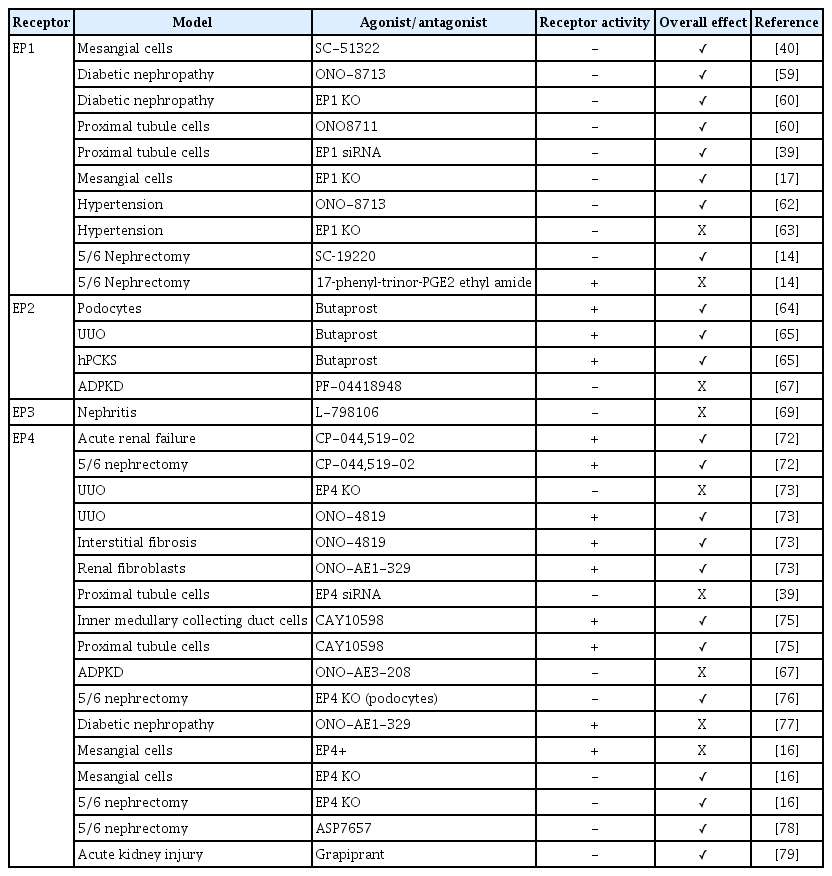

The EP1 receptor is highly expressed in the collecting duct [36–38], but EP1 is also found in proximal tubules [39], glomerular mesangial cells (MCs) [40], and podocytes [41,42] as well as in thick ascending limbs [43]. Activation of EP1 increases intracellular calcium, thus contributing to the natriuretic and diuretic effects of PGE2 [43-45], as well as playing an important role in the regulation of blood pressure [46]. The EP2 receptor is detected in vascular smooth muscle cells and renal interstitial cells. Additionally, EP2 is also expressed in glomeruli, the descending thin limb of the loop of Henle, and cortical and outer medullary collecting ducts as shown by reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction and functional studies [47–50]. EP2 stimulates adenylate cyclase and signals via the secondary messenger cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) [26]. In addition, it has been described that EP2 also can signal through β-arrestin-dependent pathways, including extracellular signal-regulated kinase and AKT [51]. The EP3 receptor is mainly expressed in the distal nephron and is most abundant in medullary thick ascending limbs and collecting ducts [52,53]. EP3 exists as different splice variants that define the preference for G-protein coupling [54,55]. It preferentially signals via Gi protein to inhibit adenylate cyclase and thereby decrease cAMP levels. However, EP3 is also involved in the regulation of intracellular calcium levels [26,34] and activation of the G12/G13 pathway, which activates Rho kinase [56]. The EP4 receptor is abundantly expressed in vascular tissue but also found in nearly all renal cell types, including proximal tubules, collecting ducts, thick ascending limb, and distal tubules [39,48]. Like the EP2 receptor, the EP4 receptor signals via Gαs to increase cAMP levels but coupling to Gi and β-arrestin has also been demonstrated [57,58]. The intrarenal distribution of EP receptors, as well as the different downstream signaling pathways, suggest distinct functional consequences of activating each receptor subtype. Next, we will delineate the role of each EP receptor in the development and progression of renal fibrosis. Moreover, the impact of EP receptor modulation on renal fibrosis is summarized in Table 1.

The role of prostaglandin E2 EP receptors in development and progression of renal fibrosis

EP1

In 1999, Ishibashi et al. [40] reported that treatment with SC-51322, a specific EP1 receptor antagonist, dose-dependently reduced high-glucose-induced DNA synthesis in rat MCs. They believed that increased MC proliferation reflected the early stages of glomerulosclerosis; thus, their findings suggested that EP1 receptor antagonism might be beneficial for treating diabetic nephropathy. Three years later, they demonstrated that selective EP1 blockade, using ONO-8713, attenuated nephropathy progression in a rat model of type-1 diabetes [59]. With regard to glomerulosclerosis, they observed that treatment with ONO-8713 markedly reduced glomerular messenger RNA (mRNA) expression of TGF-β1 and fibronectin in diabetic rats [59]. However, despite these promising results, research into the EP1 receptor and diabetes-induced renal fibrosis was virtually absent for a decade. In 2013, Thibodeau et al. [60] studied the onset and progression of diabetic nephropathy in EP1−/− mice. Their study revealed that absence of the EP1 receptor protected against diabetes-induced renal injury, illustrated in part by a reduction in mesangial matrix deposition and cortical fibronectin expression compared with diabetic mice. Additionally, they showed that treatment with ONO8711 as well as EP1 small interfering RNA (siRNA) completely mitigated PGE2-induced fibronectin expression in mouse proximal tubule cells [39,60]. In line with these results, it has been reported that fibronectin and collagen I expression was lower in TGF-β-exposed EP1−/− MCs than in wild-type (WT) MCs [17]. The exact molecular mechanisms underlying the protective effects of EP1 antagonism remain unclear; however, it has been postulated that it might be related to a reduction in reactive oxygen species and suppression of endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress [39,61]. Next to diabetic nephropathy, it has been proposed that the EP1 receptor plays a role in hypertension-related renal injury. Suganami et al. [62] demonstrated, in stroke-prone spontaneously hypertensive rats, that treatment with ONO-8713 for 5 weeks improved renal function and attenuated the development of interstitial fibrosis. Conversely, in mice with long-standing hypertension, it was demonstrated that absence of the EP1 receptor was associated with a reduction in glomerular filtration as well as ultrastructural injury to podocytes and glomerular endothelium [63]. Interestingly, in both studies the impact of EP1 receptor modulation was observed despite persistent hypertension. Recently, Chen et al. [14] reported that antagonizing the EP1 receptor with SC‑19220 improved renal function and fibrosis in mice subjected to 5/6 nephrectomy (PNx), most likely by reducing ER stress. Moreover, they demonstrated that activation of the EP1 receptor with 17‑phenyl‑trinor‑PGE2 ethyl amide aggravated renal injury in PNx mice. Taken together, it appears that EP1 receptor antagonism protects against diabetes- and CKD-induced renal fibrosis. However, its role in hypertensive kidney disease remains unclear.

EP2

Studies regarding the role of the EP2 receptor in renal fibrosis are more recent. In 2018, Liu et al. [64] reported that butaprost, one of the older synthetic EP2 receptor agonists, attenuated TGF-β-induced podocyte injury by promoting cell proliferation and reducing apoptosis. Additionally, Jensen et al. [65] recently demonstrated that butaprost markedly reduced renal fibrosis in mice subjected to unilateral ureteral obstruction (UUO) surgery as assessed by a decrease in fibronectin, α-smooth muscle actin, and collagen 1A1 expression. More importantly, they also demonstrated that butaprost elicited an antifibrotic effect in TGF-β-exposed human precision-cut kidney slices [65]. Thus, their study provided strong evidence that the effect of butaprost may translate to clinical care since its effects on markers of fibrosis are present in UUO mice and human kidney slices [66]. The mechanisms of action underlying the antifibrotic effect of butaprost is not fully understood. Jensen et al. [65] proposed that butaprost had a direct effect on TGF-β/Smad signaling, independent of the cAMP/PKA pathway. Additionally, butaprost might mitigate ER stress [61]. Interestingly, a recent study regarding autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD), demonstrated that, while EP2 antagonism reduced cyst formation in vitro, treatment of Pkd1nl/nl mice with PF-04418948, a selective EP2 antagonist, resulted in more severe cystic disease and renal fibrosis [67]. Thus, although evidence is scarce, all of the current studies, including work in human precision-cut kidney slices, support the notion that EP2 receptor activation can mitigate renal fibrogenesis.

EP3

Using single-cell RNA sequencing, Wu et al. [68] demonstrated that the EP3 receptor is highly expressed in myofibroblasts isolated from a human rejected kidney allograft biopsy (http://humphreyslab.com/SingleCell/). This might indicate that the EP3 receptor is involved in myofibroblast activation and/or ECM production. Yet, studies on the role of this receptor in renal fibrogenesis are absent. In a mouse model of nephrotoxic serum-induced nephritis, PGE2 administration restored renal function and mitigated renal damage; however, this positive effect was completely abolished by exposure to the EP3 receptor antagonist L-798106 [69]. Suggesting that EP3 receptor activation might protect against renal injury. Furthermore, EP3 receptor depletion was associated with cardiac fibrosis and reduced MMP-2 expression and activity in mice [70]. In contrast, using gingival fibroblasts, it was demonstrated that EP3 receptor activation increased the gene and protein expression of connective tissue growth factor (CTGF) [71], which could promote fibrogenesis. Clearly, the role of EP3 receptor in fibrosis and its therapeutic potential remain unknown.

EP4

Of all PGE2 receptors, EP4 is most widely studied in the context of renal fibrosis. In 2006, Vukicevic et al. [72] demonstrated in a rat model of mercury chloride (HgCl2)-induced acute renal failure that treatment with the EP4 agonist, CP-044,519-02, restored renal function (serum creatinine and blood urea nitrogen) and significantly improved histopathological outcomes (proximal tubule necrosis and total number of apoptotic cells). They also reported that EP4 agonism markedly improved GFR in rats subjected to PNx, which was associated with reduced glomerular sclerosis, more viable glomeruli, less tubulointerstitial injury, and better preservation of proximal and distal tubule structure [72]. Six years later, Nakagawa et al. [73], used EP4–/– mice to further unravel the role of this receptor in renal fibrosis. They demonstrated that UUO-induced tubulointerstitial fibrosis, as assessed by collagen deposition, macrophage infiltration, myofibroblast proliferation and TGF-β1 and CTGF mRNA levels, was more pronounced in the kidneys of knockout mice than WT mice. Moreover, stimulation of the EP4 receptor using ONO-4819 significantly reduced UUO-induced fibrosis in WT mice, but not in EP4–/– mice, indicating that the positive effect of ONO-4819 on tubulointerstitial fibrosis was mediated by EP4 [73]. Of note, the antifibrotic effect of ONO-4819 was confirmed using another model of kidney disease as well, viz. folic acid-induced nephropathy [73]. They also showed that the EP4 agonist ONO-AE1-329 significantly suppressed platelet‑derived growth factor-BB-induced proliferation of renal fibroblasts isolated from WT kidneys, but not of fibroblasts isolated from EP4–/– kidneys [73]. Furthermore, ONO-AE1-329 significantly inhibited TGF-β1-induced CTGF production by WT fibroblasts but not by EP4–/– fibroblasts [73]. This elegant work provided strong evidence that the EP4 receptor is a potent endogenous therapeutic target limiting renal fibrosis [74]. In line with these results, it was demonstrated that treatment with EP4 siRNA slightly increased PGE2-induced fibronectin expression in mouse proximal tubule cells [39]. Additionally, Luo et al. [75] reported that treatment with the EP4 agonist CAY10598 markedly suppressed TGF-β1-induced protein expression of collagen I and fibronectin in murine inner medullary collecting duct cells. They also showed that CAY10598 treatment mitigated angiotensin II-mediated NLRP3 inflammasome activation in human proximal tubule cells. Interestingly, similar to the findings with EP2 receptor modulation, treatment with the EP4 agonist ONO-AE1-329 promoted cyst growth in MDCK II and OX161-C1 cells, whereas EP4 receptor blockade in vivo increased disease severity in two mouse ADPKD models [67]. Taken together, all these studies seem to indicate that EP4 agonism mitigates fibrotic processes in the kidney. However, the role of the EP4 receptor in renal fibrogenesis might not be so clear-cut, as Lannoy et al. [67] already illustrated.

In 2010, it was shown that podocyte-specific EP4 deletion significantly reduced glomerulosclerosis in mice subjected to PNx [76]. A few years later, it was demonstrated that 12 weeks of EP4 agonist ONO-AE1-329 administration exacerbated fibrosis in streptozotocin-induced diabetic mice, as shown by increased collagen deposition and elevated gene and protein expression of various fibrosis markers, including collagen I, fibronectin, and α-smooth muscle actin [77]. Importantly, the same study revealed that the profibrotic effect of EP4 agonism was absent in interleukin-6 knockout animals [77]. In line with these results, it was shown that TGF-β1–induced gene and protein expression of collagen 1 and fibronectin was augmented in EP4-overexpressing mouse MCs, while the response to TGF-β1 was absent in EP4+/− MCs [16]. Moreover, EP4+/− mice showed fewer fibrotic lesions following PNx than WT mice [16]. More recently, Mizukami et al. [78] demonstrated that repeated administration of ASP7657, a EP4 receptor antagonist, reduced glomerulosclerosis and interstitial fibrosis in rats subjected to PNx, according to histopathological examination. The beneficial effect of EP4 receptor blockade was also seen in a mouse model of cisplatin-induced kidney damage. In these mice, treatment with the EP4 antagonist grapiprant, a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug widely used in veterinary medicine [79], markedly reduced collagen deposition and α-smooth muscle actin expression associated with cisplatin exposure [80]. Taken together, the EP4 receptor has been the greatest focus of research to develop new renal fibrosis therapies. Unfortunately, despite decades of work, results are conflicting and the therapeutic potential of the EP4 receptor remains unclear.

Conclusion

Although the role of COX-2 and PGE2 in renal (patho)physiology is well established, studies revolving around its receptors and renal fibrosis, which is the most damaging process in CKD development, remain sparse (~20 at the time of writing). Still, the current body of work is enlightening and suggests that PGE2 receptors are potentially important targets for renal fibrosis treatment. Nonetheless, more studies are required to fully unravel the therapeutic potential of PGE2 receptor agonists/antagonists. With the advent of improved translational disease models, such as human precision-cut kidney slices and kidney organoids, pre-clinical studies will provide valuable information on the antifibrotic efficacy of putative therapeutic compounds in human tissue, which will hopefully expedite the development of effective and safe therapeutics that can be used in clinical care.

Notes

Conflict of interest

All authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding

This work was supported by the Danish Council for Independent Research (grant number 6110-00231B).

Authors’ contributions

Conceptualization: RN

Writing–original draft: HAMM, RN

Writing–review & editing: HAMM, RN

All authors read and approved the final manuscript.