A case of membranous nephropathy associated with relapsing polychondritis

Article information

Abstract

Relapsing polychondritis (RP) is a rare, chronic, and potentially fatal multisystemic inflammatory disorder targeting cartilaginous structures. This disorder is frequently associated with rheumatoid arthritis, systemic vasculitis, connective tissue diseases, and hematologic disorders, but renal involvement is unusual. In the literature, associated renal pathology includes mesangial expansion, IgA nephropathy, tubulointerstitial nephritis, and segmental necrotizing crescentic glomerulonephritis. We report a case of a 49-year-old male found to have RP and nephrotic syndrome, with confirmed membranous nephropathy on kidney biopsy. He responded well to corticosteroids and cyclosporine. This is the first case of renal associated RP confirmed by renal biopsy in Korea. Membranous nephropathy associated with RP has never before been reported.

Introduction

Relapsing polychondritis (RP) is a rare autoimmune disease of unknown etiology, characterized by recurrent inflammatory episodes primarily affecting the auricular, nasal or laryngotracheal cartilage. Other noncartilaginous tissues such as the ocular, audiovestibular, kidney, and vascular systems may also be affected. Several reviews of the specific clinical manifestations found in RP have been published (ocular, otorhinolaryngologic, cardiac, and respiratory). Renal involvement has rarely been reported. We treated an unusual case of a 49-year-old male with nephrotic syndrome diagnosed with RP. We describe the unique features of this case and provide a review of the literature on renal-associated RP.

Case report

A 49-year-old man was admitted to our hospital in June 2010, with a 1-month history of generalized edema, weight gain, and dyspnea on exertion. His past medical history was significant for diabetes mellitus and hypertension for 12 years. Additionally, he was diagnosed with RP 9 months earlier, in September 2009, after presenting with recurrent scleritis, bilateral auricular chondritis, and nasal chondritis. He had been on corticosteroid therapy for RP, but discontinued his medications 4 months prior to admission. On physical examination, his blood pressure was 130/80 mmHg, pulse was 78 beats/minute and body temperature was 36.4 °C. His left eye was injected. He had a notable saddle nose and auricular distortion (Fig. 1A–C). Both legs showed gross edema.

Clinical findings compatible with the diagnostic criteria for relapsing polychondritis. (A) Red conjunctiva and opaque cornea caused by repeated keratoconjunctivitis. (B) Saddle nose deformity caused by repeated nasal chondritis. (C) Deformed auricle caused by repeated auricular chondritis.

Laboratory findings consisted of blood urea nitrogen 15.1 mg/dL, creatinine 0.68 mg/dL, and serum albumin 1.2 g/dL. Urinalysis showed 3+ proteinuria and urine microscopy was unremarkable. A spot first morning urine protein-to-creatinine ratio was 13.23 (spot urine P/C, normal < 0.2 g/g), consistent with nephrotic range proteinuria. All other serologic parameters, including complement factors C3 and C4, antinuclear antibodies, cryoglobulins, anti-dsDNA antibodies, and perinuclear/cytoplasmic anti-neutrophil cytoplasm antibodies, were negative or normal. Chest X-ray showed hypervolemia, with bilateral pleural effusion.

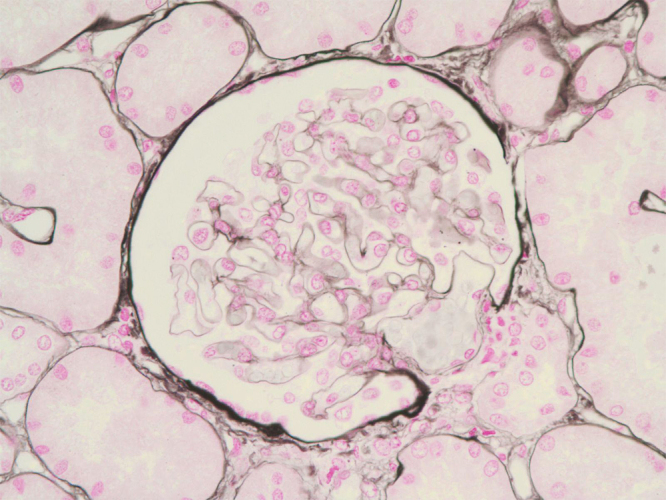

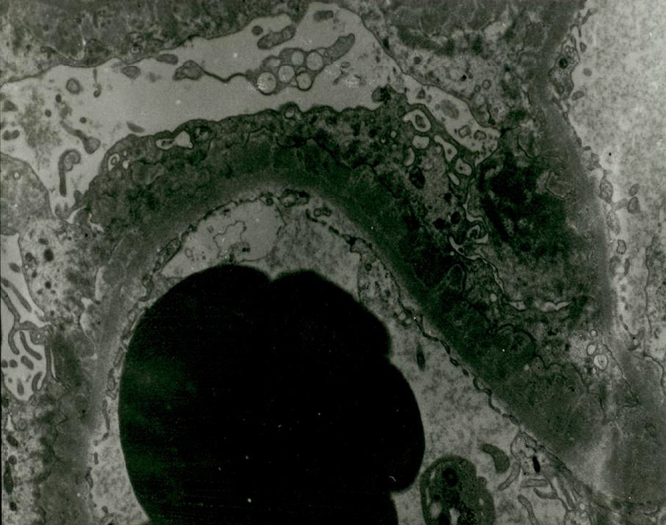

At that time, the necessity of a renal biopsy remained unclear, as the patient’s proteinuria could have resulted from diabetic nephropathy in the setting of a longstanding history of diabetes mellitus. However, ophthalmic examination revealed no evidence of diabetic retinopathy, only episcleritis, for which prednisone was initiated. Our medical team recommended performing a renal biopsy, but the patient and his family refused. In the interim, diuretics and antihypertensive medications, including an angiotensin receptor blocker, were prescribed. In the outpatient setting, his proteinuria increased (from 8.4 to 26.8 on spot urine P/C) as his doses of prednisolone decreased (from 40 mg to 5 mg). We again recommended a renal biopsy, explaining to the patient that his proteinuria could be associated with RP. He was readmitted 9 months after his first admission to nephrology, in March 2011. His AM spot urine P/C ratio was 21.6 at that time. Percutaneous renal biopsy of the left kidney, performed under ultrasound guidance, showed nine glomeruli. Capillary basement membranes, of relatively normal thickness, were observed on light microscopy (Fig. 2). Direct immunofluorescence studies demonstrated the presence of IgG in a granular fashion along the basement membrane (Fig. 3). Ultrastructural studies revealed electron-dense deposits in the subepithelium (Fig. 4). Although they also showed focal mesangial expansion and nonspecific capillary wall thickening (Figure not shown), which could be consistent with the findings of early stage of diabetic nephropathy, we did not think these were the main lesions causing the massive proteinuria in the patient. The patient responded well to prednisolone (1 mg/kg/day), which was later tapered, due to a concern about iatrogenic Cushing disease and long-term complications of using high dose steroids. Cyclosporine (3 mg/kg) was initiated to when the steroid was tapered. At an 18-month follow-up visit, the patient continued to respond well to cyclosporine (150 mg bid) and low dose prednisolone (10 mg/day). No relapse was observed during this follow-up (spot urine P/C 0.6, serum creatinine 0.82 mg/dL in September 2012). The patient’s progress was summarized in Table 1.

Light microscopy. Capillary basement membranes of relatively normal thickness are shown (silver methenamine; magnification × 400).

Immunofluorescence microscopy. Granular fluorescence and IgG deposits in the basement membrane are shown (magnification × 400).

Electron microscopy. Electron-dense deposits in the subepithelial locations are shown (magnification ×5850).

Discussion

RP is a rare autoimmune disease, characterized by recurrent bouts of inflammation and permanent destruction of cartilaginous structures such as the ears, nose, joints, trachea, and larynx. Other tissues high in glycosaminoglycans, such as the heart, blood vessels, inner ear, cornea, and sclera, can also be affected [1]. As RP is a clinically diagnosed entity, there are no specific laboratory tests available to establish the diagnosis. The diagnostic criteria have been described by McAdam et al [1]. Our patient fulfilled these criteria, having recurrent auricular chondritis, hearing loss, nasal chondritis, respiratory tract chondritis, and ocular inflammation.

Renal complications of RP are rare. About 22% of patients with RP develop some type of renal lesion with microhematuria, proteinuria, or abnormal kidney biopsies [2]. Chang-Miller et al described patients with renal involvement as having worse survival outcomes and an increased frequency of extrarenal vasculitis and arthritis in comparison to RP patients without renal involvement [2]. Biopsy-proven nephropathy has been reported in < 10 cases [3] and has never been reported in Korea. Renal pathology may manifest as mesangial expansion, IgA nephropathy, tubulointerstitial nephritis, segmental necrotizing crescentic glomerulonephritis, and minimal change disease [3]. In previous reports [2], [3], immunofluorescence microscopy of kidney biopsy specimens inconstantly shows IgA, IgG, IgM and complement deposits in the basement membrane, capillary walls and mesangium, suggesting that immune complexes may play a role in the pathogenesis of the glomerular lesions of RP. We think this may also be the main pathogenetic factor of our case.

As far as we know, this is the first case of membranous nephropathy associated with RP ever reported.

Our delay in diagnosis stemmed from the patient’s 12-year history of diabetes and his reluctance to undergo an invasive procedure. Eventually, a renal biopsy was performed for the following reasons: (1) there was no identifiable diabetic retinopathy; and (2) the amount of proteinuria responded to increased doses of prednisolone prescribed by his ophthalmologist.

Treatment of RP consists of empiric trials based on clinical presentations. Because of the rarity of the disease, no clinical trials have been performed. Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) alone are adequate for patients with mild auricular or nasal chondritis. More serious manifestations require corticosteroids, either oral (0.5–1 mg/kg/day) or intravenous pulse therapy in doses of 1000 mg/day. Various immunosuppressive agents, such as cyclophosphamide, azathioprine, methotrexate, cyclosporine, chlorambucil, and others, have been used successfully in treating renal involvement in patients unresponsive to conventional immunosuppressive agents [2], [3], [4].

Our patient responded dramatically to prednisolone (1 mg/kg/day), but we had to decrease the steroid dose and instead add cyclosporine (3 mg/kg) to prevent long-term complications of high dose prednisolone, which was prescribed for ophthalmologic and respiratory manifestations. Currently, he has continued to do well on low-dose oral corticosteroids (prednisolone 10 mg/day) and cyclosporine (150 mg bid/day, 3 mg/kg/day) without relapse during an 18-month follow up period.

RP is an intermittent, but progressive disease. Common causes of death include airway or cardiovascular complications, secondary infection, renal failure, or systemic vasculitis. The survival rate was initially reported to be 70% at 4 years [5], but with the advent of newer and better immunomodulatory therapeutics, it has now been reported to be 94% at 8 years [6].

In summary, a 49-year-old male patient was diagnosed with RP 3 years prior to presentation and subsequently developed nephrotic syndrome 9 months later. He had been hospitalized for respiratory complications several times before a renal biopsy was performed. He was diagnosed with membranous nephropathy associated with RP. High dose corticosteroid and cyclosporine were prescribed initially and the patient was maintained on a low dose of prednisolone and cyclosporine without relapse. In view of the potentially progressive nature of glomerular disease with RP, renal status should be investigated in all patients with RP.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.